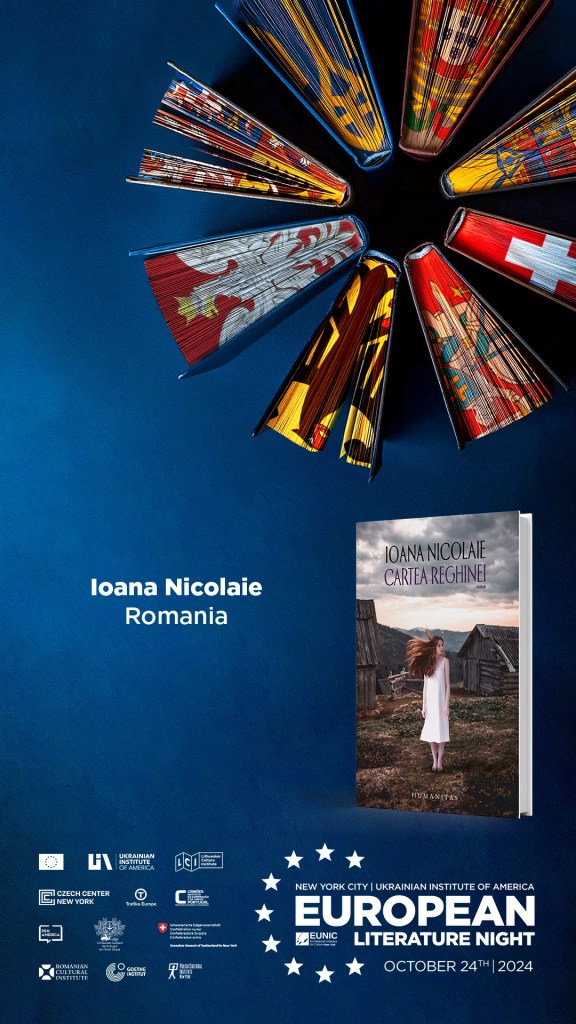

One of the most original and powerful voices in contemporary Romanian literature, IOANA NICOLAIE is the author of six novels, five volumes of poetry, and ten children’s books, which have won her numerous literary awards. Her novel, Cartea Reghinei / The Book of Reghina was the winner of the 2020 Radio Romania Cultural Award, Observator Lyceum Prize, National Prose Prize Iași, and Book Agency Award. She has been translated into several languages and has participated in numerous national and international literature festivals all over the world.

The Book of Reghina, published in Romania by Humanitas, is going to appear soon with the prestigious Italian press, La Nave di Teseo. The book’s heroine, Reghina, is a female Job from a northern Transylvanian space where the miraculous insinuates itself into the common order and the communist past still thwarts people’s destinies. She is the mother of twelve children together with whom she makes up “a body weighing a thousand pounds.” The narrative is dense, deeply moving, sequenced in episodes: a match, a wedding, the first night of love, the first beating from her husband, the first child, the next twelve.

On October 24, 2024, Ioana Nicolaie will represent Romania at the European Literature Night in New York, where she will join a group of writers and translators from all over Europe: Romain Buffat (Switzerland), Paulo Rodrigues Ferreira (Portugal), Rimantas Kmita (Lithuania), Magdaléna Platzová (Czechia), translators Ross Benjamin (Germany), and Grażyna Drabik (Poland).

Dear Ioana, welcome to this blog and, I must add, welcome to New York! In fact, as you’ve been here for more than a month, together with your husband, the writer Mircea Cărtărescu, who teaches a course at Columbia University, it would seem that you’re already a bit of a New Yorker. How have you connected with the city’s energies and what book would you write about it?

A book entitled Future, there’s no doubt. When you get to the 64th floor of One World Trade Center and see the fluffy clouds right in front of your face, while the Brooklyn Bridge is down there, far away, like a toy on a blue surface, you can’t be anywhere but in the future. The first week I spent in New York I had a sense of unreality – I found a green lake in Central Park, went down to Times Square, went to see the Dakota Building. Then there was the Chelsea Hotel, where the extraordinary poet Andrei Codrescu took us, and the houses where Allan Ginsberg or Ted Berrigan lived, and the museums, and Lincoln Center and so much more. Some favorite things in New York? The campus of Columbia University, the people in the subway, a little church in Harlem, the bamboo garden of the writers Carmen Firan and Adrian Sângeorzan, the audience that comes to the events of the Romanian Cultural Institute in New York, the room at MoMA where you can make a phone call to listen to poetry.

You started your writing career as a poet, then, after the publication of an unclassifiable book about pregnancy/motherhood called The Sky in the Belly, you turned to prose. But anyone who knows your writing can see that your poetry is narrative, while your novels and all your other prose books have a strong poetic vein. Why this mix?

What is a poet? Someone who writes about what they feel, focused, ambiguous, and then crams texts arbitrarily between two covers? No, that wasn’t for me. The poet in my mind liked the stories, and the challenge, and the sense of freedom you get when you know that, in fact, each poem is like a fragment of a larger story. I’ve been pushing the boundaries between genres a bit, playing with literary forms. I published a couple of volumes of this kind, until the poet in my mind realized that she was actually a prose writer. How could she not be? I was born in the Northern part of Romania, in Transylvania, in a family of twelve children. I was the fourth. I lived from the very beginning in a dimension of the fabulous, through the stories and ancient beliefs, but also in one of the contradictory, due to the aggressive way in which the communist regime changed the world, but also in puzzlement – how come that we are all living in a prison? –, but also in ignorance, as the new generations were learning a falsified history, and also in powerlessness, as we were all trapped in a dictatorship. My volumes of prose are about how the individual is crushed by the history that contains him, about what communism meant, about how women were forced to bear children (the dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu wanted to increase the birth rate at any cost), about the lack of opportunity of the marginalized, about lies and manipulation. They are also about individual heroism, about beauty without which we could not live, about sacrifice and love.

The novel I just finished here, while in New York, is also a bitter love story between two young people. The girl disappears at some point and it is only after the fall of communism that we learn that she was one of the two hundred thousand ethnic Germans sold by the communist regime to the Federal Republic of Germany. The Germans in Romania were only allowed to leave the country after the adoptive state paid a sum of money. In the last years of the dictatorship, the freedom of each ethnic German amounted to 8,500 marks. As for the Romanians, they couldn’t even dream of leaving the country, no one defended them, no one wanted them, they had no passports, the borders were permanent and huge.

The Book of Reghina, the novel you will be presenting at European Literature Night, is the drama of a woman, a “heroine mother” with twelve children from a traditional community, still living, in the middle of the 20th century, in a world governed by archaic laws and mentalities. What is it about this book that you think might appeal to English readers and what might they find relatable in it?

108 months… at some point this thought came into my head. I mean nine years. Well, my mom was pregnant for nine years. How did that happen? And more importantly, how was it possible for a girl from a world that looked like Paradise to be married at sixteen and then go through hell? I, as this woman’s fourth child, I, the one called in the book “the girl who only listens” (the other children have no names either), had to write the story. I was the witness. I knew well what it meant to be just a part of a thousand-pound body like that of the heroine I named Reghina. It was my hardest book to write, because my mother had had a stroke and I feared she would pass away before I finished the novel. The first thing I did when I wrote “The End” was to call my sister who was standing next to her and ask her to tell my mother, because she would surely understand, that I had written her book. And she understood.

As to how The Book of Reghina might appeal to audiences from other cultures, I could refer to Umberto Eco who talked about the “ideal reader”. What is an “ideal reader” in Eco’s vision? The reader who has exactly the same life experience and inner encyclopaedia as the author. Of course, such a reader does not exist. So why do people read? Why do they go to shows? Why are they movie buffs? To enjoy, to live other lives, to know more, to discover, to learn. We can imagine novels as planets that are similar to our own, the one we know very well, but above all different. I think that difference is what matters. For it it’s worth traveling, to breathe a different air, to feel how things are under a different sky. The Book of Reghina is a surprising planet, with unusual landforms, at least some of which I think have never been mapped before.

Reghina’s book subjugates its reader from the very first pages and carries him hypnotically, breathtakingly, over the ‘summer of three years’, over people’s destinies flowing from one to another over the span of a century marked by the permanence of suffering. – Alexandru Tabacu, Contrafort

Three of your most recent novels have been put by critics under the umbrella of a “Northern family saga”. And some of them have found in these books a predisposition towards magical realism. I would like to ask you to describe a little bit this fabulous Transylvanian North from which you draw your roots. And then I’d like to find out if the source of the magical realism in your prose can be directly linked to this space. Is it autobiographical or bookish?

My grandfather on my mother’s side once told me how, while on a mountain, he managed to immobilize a fairy who would otherwise have killed him. She asked him to let her go and told him, as in fairy tales, of course, that she would grant him a wish. What wish? And my grandfather asked that he and his descendants – me included, having lived in Bucharest, Vienna and Berlin, and now, for two months, in New York – should not be afraid of wild animals. I smile as I write this. As a child, I was sure that fairy was real. How could I not use this imaginary later in literature? Gabriel García Márquez once said that in his books there is nothing magical, everything is real. So in my novels, where there are foxes, fairies or other disturbing beings, where there is always a trail of mystery, it’s not so much fantasy as a kind of inner truth that is not only rational but also fantastic. What else have I put in my novels to balance their serious core? Nostalgia, romance and, to the best of my ability, beauty.

Critics also discovered in your novels elements that made it possible to compare them with texts by William Faulkner or Cesare Pavese, and among Romanian writers, Liviu Rebreanu or Max Blecher. Which authors have had the greatest influence on your writing?

All of them have meant a lot to me, but many more. Faulkner, of all writers, I think is the greatest master of voices. Shoulder to shoulder with him is Virginia Woolf. How can you not find this power of theirs extraordinary? How can you not admire them? From the very beginning, I was attracted to the subjective narrator who can tell a story like no one else. I use it in almost all my novels, and it’s not at all easy, because it inhabits all kinds of minds. In The Blackthorn I lived in the mind of an atypical child who spends a few years in a children’s home, in The Book of Reghina I put myself in the mind of someone who, being elderly, suffered a stroke and yet has to tell her life story, and in the latest novel, which is about to be published, I went even further, because the point of view is that of someone who has already died, my elder brother, Radu.

The Book of Reghina is your most awarded book, that attracted a lot of praise. But if you had to choose a favorite book yourself, which one would you immediately think of?

Painting the Water, because I finished it here, in New York. Uh, no, The Book of Reghina. I think The Blackthorn, though. No way, Onwards, because this novel is really about me and my real memories of communism. So… I can’t choose. There’s a continuum of intensity and lived life in all my books. I’m happy to have signed this year with La Nave di Teseo, a major Italian publisher, for the translation of The Book of Reghina. I hope that in the future it will also be translated into English so that it can be read in the United States.

I see your literature as an organic whole in which the same themes are to be found everywhere, including in the children’s books. Tell us about the importance of children’s literature in the context of your work, but also about your creative writing courses for teenagers and your other educational and humanitarian projects.

I like writing for children, because in children’s literature I can not only let my fantasy free but I can also choose any literary formula. In my poetry books, for example, I have never written rhyming rhymes, but in my books for children I’ve had no barriers. I also practised genres considered “inferior”, such as science fiction. However, the stakes of my writing lie in the novels I mentioned above, in their serious subjects, in their engagement with the world, not in escaping into fiction.

The Melior Foundation, of which I am a founding member, is also in this direction, of the duty I feel I have towards others. For ten years, the Foundation has been taking the most beautiful books of literature to schools in isolated Romanian villages, where children who often have no books at home learn. And, because I’ve been thinking for some time that young people who write literature need support, over the years I’ve managed to bring together a group of young poets, some of them beginners, others approaching their debut, called “The Liternauts”. We meet weekly on Zoom, we discuss the fantastic poets of the world and then I listen to them read poetry. I am convinced that before long their names will mean something in Romanian literature. Since I’ve been here in New York, I’ve talked to them about Frank O Hara, Andrei Codrescu, Allan Ginsberg, etc.

Over the years, you have participated in many international festivals and your texts have been translated into several languages. In which country have you had the most unexpected reactions from your readers?

I’m grateful for every language my books have reached, it has always seemed like a gift to me that they had the chance to appear in another culture. I’ve been to public meetings, I’ve got reviews – whether in Germany or Sweden or Bulgaria –, I’ve felt overwhelmed every time. If one reader discovers that a book written by me is about him or her, a book written by someone from far away, from another place, that he or she doesn’t know, that’s enough for me. I’ll hope that one more reader will come along, and then one more, as has happened in my own country, where each of my books sells many thousands of copies.

At the end of this interview and in anticipation of your first encounter with the demanding New York audience, I would like to ask you to leave here a small gift, a short text in English translation, for the readers of this blog who are eager to meet you.

Another book I didn’t mention above is The Heart’s Core, a book that is difficult to categorize. It has been presented as a collection of short stories, but it is also a kind of novel. The narrator, a sort of alter-ego of mine, brings to light some real-life events, some traumatic, some poetic, some mysterious. For English-speaking readers I’ve chosen the story “The Jacket”. It takes place on a train in Romania, and it has at its center a very young journalist who… The rest can be read below, translated into English by Andreea Iulia Scridon.

THE JACKET

What does a face look like reflected in a computer screen? When slanted light falls upon it, upon its curves, so that nothing remains of the studio in which you live, on the tenth floor, in a neighborhood with blocks of flats pasted against each other, where only once, after a sleepless night, the sun, as if it were a fist, suddenly bloodied the windows. It looked a bit like the one I saw through the train window at sunset. What exhaustion! I said to myself. And how much summer, how much light, how many hours in which you only want to catch your breath. To huddle into yourself until the sound of train wheels turns to dust.

“Bring me at least five materials!” I heard. Everything was arranged, in Cluj someone would pick me up from the train station, the schedule was partially completed, I would be reasonably hosted. As for the journalist job, I was going to do that myself, maybe a little better than I had lately…I swallowed the lump in my throat and saw to my clear-head pages. For more than a month I’d been reading articles without understanding anything, mechanically correcting the missing letters, inserting commas, returning to a sentence two or three times. By the end of the shift, I would smoke an entire pack of Vogue. After the first day in which I didn’t turn in my material, there came another, and then another. I was no longer attending press conferences. Once I took the subway in the opposite direction, another time I wandered I don’t know how long through the Știrbei Palace without finding the door behind which a heated discussion about educational reform was taking place.

“Is this seat empty?”

I didn’t bother to answer, just gestured yes. How could it have been taken if there was hardly anyone in the first class carriage? And the controller hadn’t even gotten to my compartment. The newcomer must have been about my age. Maybe not exactly 24, but close anyway. It didn’t take me more than a glance to figure that out. He’d put his bag correctly in the overhead space while I still had my backpack on the seat in front. I had nothing in it, just a thin black blouse, smart enough to show up in for interviews. The forecast said that it was hot in Cluj too, it’s true that it wasn’t quite 95 degrees as in Bucharest. I had hastily gathered my toothpaste, toothbrush and two or three other necessary things. I just made sure about the tape-recorder, lest I forget the batteries. I took two spare tapes, as if they were of any use. I also had the camera, with my film in it, so I could illustrate the reports.

I had sat down at the window, watching reality decompose. Later, after it grew dark, I would stretch out my seat and that which was in front to make a bed of sorts. The narrow kind, where, if it’s just you, you can pull your knees up to your chin. And you can doze off, without leaving the light on, as you do in the little room where, every evening, you hear the sobs of the girl living in the studio below you. You know she broke up with the actor she loved, you heard their argument.

I’m not her, I revolt. Me….When I leave the newsroom, I catch the 335 that takes me from the Press Office directly to Mihai Bravu Station. There I cross the street and arrive at…“Eye Cabinet”. How many times I laughed with him about this place! Once I told him a story I had read that morning, on the bus. An elephant bends down to drink water from the stream and loses an eye. It slips from between his eyelids like a giant bead. The waves swallow it, and he desperately begins to search. He stomps his feet, kicks up his trunk, stirs everything up, until the water is filled with gravel and plant debris. “Calm down!” call the fish. In vain, he does not hear. “Where is the eye, where?” “Calm down!” cry the animals gathered on the shore. But he doesn’t hear them. Where is the eye? How can it live without him? After a while he gets tired and for a few moments stops struggling. And he understands at once. It suffices to stand still, as the eye comes to the surface by itself.

When I told him this story, he had just barely moved in with me. Not for good, but you know, as a test. He had brought a few things, a few books, and my happiness was inestimable. I felt it like an upheaval. The sheets were never smooth again. On Saturdays we would take a trolley and ride a few stations at random. Then we would come back on foot, look at the crumbling facades, we would go around a small street where the lilac had burst out in the unspeakably warm spring.

“Tickets out!”

The controller opened the door noisily. A cool breeze swept in. After the last two weeks, always 95 degrees, it felt like a blessing. It was terribly hot at night in the studio on the top floor, just below the block’s terrace. I’d open the windows in vain, at most mosquitoes would enter through them. When I didn’t want to think about anything, I would start scrubbing the tiny stove, so grimy and stained that it could never be cleaned. I wiped the surfaces tirelessly, until my skin peeled. If I could have, I would have painted the smoke-blackened walls too. I struggled to remove the stains from the ceramic, to glaze something that would never be whole again. But I avoided the balcony. From places like that, I knew, certain people could fall. Since we didn’t have a washing machine, we washed our clothes by hand. If I was left alone, there weren’t many to deal with anyway. Then I would dry them on a line in the bathroom.

The young man got up and went out into the corridor. That was it, by now it was night, the train had torn through the pitiful suburbs, unreal groves, hills, mountains, the plateaus of Transylvania, nameless stations. I closed the window because it was getting colder and colder. My t-shirt had dried on me. At least it wasn’t stuck to my body anymore.

“You could win any beauty pageant!” a colleague told me. “Tell me how you stay in shape!”

What should I have told her? That since the day I’d found the message written in capital letters on the computer screen, I’ve only bought a single loaf of bread? I only ate one slice, so I decided not to buy any more. I didn’t use potatoes anymore, nor pumpkins, beans or eggplants. In the evenings I would boil an egg and put a tomato next to it. I had to live, otherwise how could I go on? How could I tremble maddened in the waves? After losing ten pounds, I ended up in the emergency room with hypocalcemia. I received infusions, reprimands and nutritional supplements. All around, the elevator, the floors I went up and down on the streets, and even the sky were still full of mop-water. I had to stop though. So I bought something from the store downstairs and made myself an oriental salad. I ate it all.

The young man came back, opened the door carefully, as if he didn’t want to disturb me. He sat down in his seat just as silently. It was getting colder and colder in the compartment. My poor t-shirt had no way of defending me. I couldn’t compromise my interview blouse. If I came back without materials, I didn’t think they would have kept me in the newsroom. I didn’t even know how they had tolerated me for so long, how they had never called me into an office to tell me anything. And when they did, look, they sent me to Cluj, they even established my contacts, they gave me everything. At 10 o’clock I had a meeting scheduled with a dean. Therefore, I needed to rest.

I got up to pull the armchair before me. There was no need, the young man with whom, as never before on a train, I had not exchanged a single word, opened it in an instant. Only then did I look at him. He had delicate features and short hair. Probably a student, I thought. Although he might as well have been a computer guy or a salesperson. A handsome boy who, like me, wouldn’t utter a word. For the best. I curled up facing the door and he put down his book and turned off the light. For a while I lay with my eyes wide open in the darkness. Why wasn’t he spreading his seat out?

I could see his profile in the light of the corridor. I suddenly realized that I felt no fear. It was the first time on a train that I didn’t care at all what would happen. If you sleep, everything is erased, everything. If you sleep, forgetting comes. So I closed my eyes, I would have glued them if I could have. The wheels were whirring in my head, and I prayed for oblivion, for oblivion to come once and for all.

I woke up suddenly, from the movement. I came to quickly, but didn’t make any gestures. I could feel myself shivering with cold, my thin flared trousers and t-shirt might not even have been there. The young man stood up and had already taken the step that separated him from me. Now he leaned over slowly. I felt his breath on my face. But he only touched me with his jacket, which still retained his warmth. He placed it gently over my back. I left it there, without moving, and after what seemed like an infinitely long time, it was finally quiet. Finally, this coat had kicked the debris aside! Look how it had waited for me, not only for that trip, when I would return with the required materials, but for so many other times when I would struggle with who knows what evil that appeared out of nowhere on my path.

The young man, in his yellow t-shirt, didn’t sleep all night. We looked into each other’s eyes only once, when I thanked him, before I rushed off towards life.

Interview conducted in Romanian and translated into English by DACIANA BRANEA

Short story translated into English by ANDREEA IULIA SCRIDON